Quality control is one of the most critical aspects of profitable and sustainable fresh produce operations. The safety of the fruits and vegetables we eat relies on accurately inspecting, testing, and grading standards and processes.

In today’s globally interconnected food economy, quality control tests are performed at several stages throughout the supply chain, from cultivation and harvesting to processing, packaging, transportation, and distribution.

Quality control processes are designed to not only ensure quality and shelf life are maximized, but also to comply with increasingly demanding regulatory and food safety complicance standard. This resource page is a compilation of some of the resources and knowledge Croptracker’s support staff have amassed during our 20+ years supporting the fresh produce industry to help our users meet these goals.

Core internal Quality Control metrics for fresh produce

Quality control in fresh produce relies on replacing subjective opinions with objective, quantitative, and traceable measurements. Objective quality attributes determine the product’s appeal, flavor, and resilience throughout the supply chain. The following is a list of the most critical and common objective QC parameters used in grading, sorting, pricing, and predicting the consumer quality of fruits and vegetables:

Brix / Total Soluable Solids (TSS)

Brix, or Degrees Brix, is a measure of the total soluble solids present in the fruit. Total Soluble Solids (TSS) are primarily made up of sugar (usually at least 80%) but may also include soluble acids like citric acid, vitamins like A and C, or other compounds. Generally though, when we talk about Brix values, it's about sugar. Brix testing is done at various points in the fruit's lifecycle, in preharvest testing it is often used as part of a maturity index. In the post-harvest world, Brix testing is used primarily to objectively assess flavor and sweetness of produce.

Acidity

Acidity testing in fresh produce quality control refers to the measurement of the total amount of organic acids present in the fruit or vegetable. This is typically done through a method called titratable acidity (TA). Titratable acidity measures the total acid concentration in the food, as opposed to pH which only measures the active hydrogen ion concentration (acid strength). TA is a better indicator of the tartness or sourness of the product, which is crucial for flavor. Acid content naturally decreases as most fruits ripen, as acids are often converted into sugars. Measuring TA helps determine the optimal harvest time and stage of maturity.

Brix / Acid Ratio

The Brix / Acid ratio, also known as the Sugar-to-Acid ratio, is a critical quality index that combines Titratable Acidity (TA) and Degrees Brix. This ratio is one of the most reliable indicators of the eating quality and maturity of many fruits, especially citrus, grapes, and tomatoes. A higher ratio generally indicates a sweeter taste, which is preferred by most consumers, because it means there is more sugar relative to the tart-tasting acid. Regulatory and industry quality standards often specify a minimum Acid/Brix ratio that fruit must meet before it can be harvested, packed, or sold to ensure a consistent and enjoyable consumer experience. The ratio is calculated by simply dividing the Brix value by the Acidity value

Starch

Starch is a type of carbohydrate found in various plants, including apples. During the ripening process of apples, the starch gradually converts into sugar. The level of starch in an apple is used as a metric to determine its ripeness, with higher starch levels indicating a less ripe fruit. A critical preharvest test in the apple industry, the starch iodine test is the most common method of calculating ideal harvest windows for apples going into storage.

Dry Matter

Dry matter measurement represents the total solids in a piece of fruit, including starches, proteins, sugars, fiber, and carbohydrates. A dry matter measurement is most simply explained as the total weight of the fruit, minus the water content. Dry matter accumulation changes throughout the fruit growth cycle and is used as a maturity indicator in some climacteric fruits. Dry matter testing is typically done by weighing fruit samples, then dehydrating them and weighing them again, subtracting the dried weight from the fresh weight to determine the dry matter ratio. Non-desutructive testing methods for dry matter testing are being embraced more frequently to speed up this process and enable larger sampling sizes.

Pressure / Firmness

Firmness / Pressure testing assesses the internal pulp firmness of a given fruit, which corresponds to the crisp, crunchy experience of eating fresh fruit. The main method of testing firmness is using a penetrometer, which is a device that measures the pressure and compression needed to puncture the flesh of the fruit. Durometers are alternative testing tools that do not puncture the fruit but similarly measures the resistance of the fruit or vegetable flesh to compression. Commercial fresh produce QC operations rely on standardized units of measurement, primarily pounds-force (lbs or lbf), Newtons (N), and occasionally kilograms-force per square centimeter kgf/cm2.

Essential visual Quality Control metrics for fresh produce

Often when consumers think of fresh produce QC metrics, they are not typically thinking of a specific Brix number or the starch scale score, they are referring to the external and visual qualities of a piece of fruit. Although many of these metrics don’t impact the taste of the fruit, visual characteristics, like color and shape, have a huge impact on the marketability and profitability of fresh produce.

Color

Color changes as fruit matures and ripens, and judging the ripeness of fruit by the external color is one of the oldest methods in the book. Different crops have different ripening processes, and the external color of the fruit isn’t always the most important metric. Internal color assessment can be used to track maturity and ripeness in types of fresh produce that don’t change color externally.

Color is also one of the most important factors for consumer acceptance of produce, so consistent color metrics are a critical part of a quality control assessment. Fruit color can impact both the grade and price of harvested fruit, and in some cases, postharvest color development needs to be induced. Quality Control experts will often have reference color guides to help them make color assessments from samples, though these cards are not always reflective of real life color and conditions and must rely on the accurate color vision of the person doing the assessment. Recently, portable tools for color assessment have been gaining popularity to help better handle this subjectivity.

For some fruits, the color during harvest is not the target color for retail. Bananas and citrus for instance are often picked green before they ripen on the tree, so that transportation and ripening time can be better aligned. Citrus in particular is often tightly color controlled using Degreening processes.

What is degreening?

When a lemon ripens and acquires that signature lemon yellow color, this is the process known as "degreening". The lemons lose their green chlorophyll during the cold nights on a tree as it ripens. However, in some climates, the degreening process may not be fast enough to color up the fruit before it ready to be harvested. When this happens degreening needs to be induced through post-harvest treatments.

Citrus destined for degreening is assessed by Quality Control staff and the length of time the lot of fruit will spend in the degreening rooms is determined by how green the fruit is and how long it will take to reach the desired color. Degreening rooms are sealed rooms that use ethylene gas at measured levels, enough to leach the chlorophyll from the fruit skin, but not applying too much so as to over ripen the fruit.

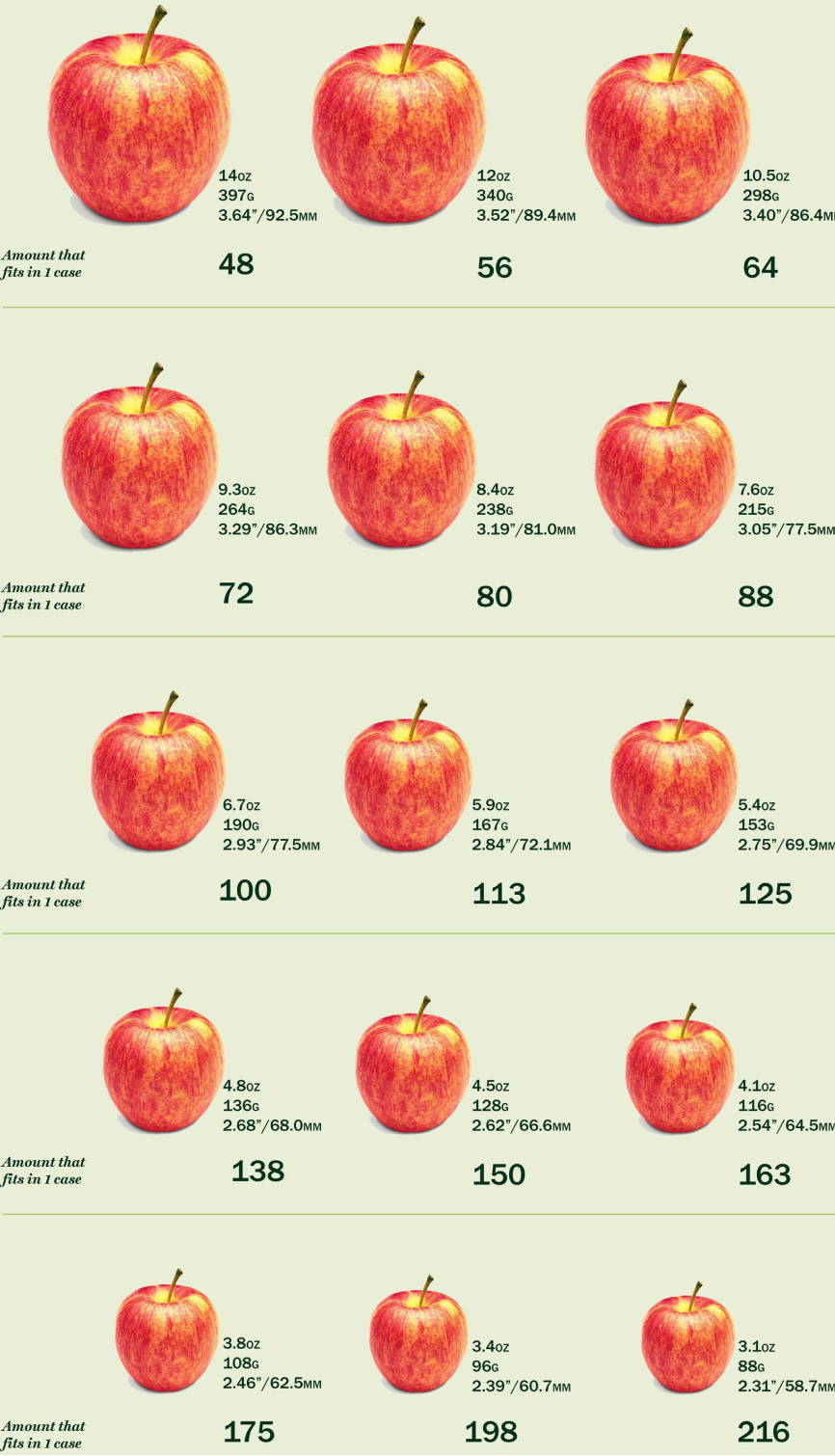

Size / Shape

Size and shape grading are crucial quality control steps in the fresh produce industry, primarily aimed at achieving market uniformity and consistency. This process begins with defining standards, often set by regulatory bodies, that specify the acceptable dimensions (like diameter or weight) and the characteristic form (or 'well-formed' shape) for a particular fruit or vegetable variety.

Prior to fruit heading to storage or to packing, trained workers visually inspect and predict how the lot of fruit will pack out. They can use a variety of tools and references to help with this process including ring sizers, defects shape guides, and more sophicticated digital size and shape assessment tools like Harvest Quality Vision.

Modern packing houses use sophisticated, high-speed technologies to automate the sorting and culling of fruit by size and shape. These systems include mechanical sizers, which use physical mechanisms like divergent rollers or weight scales to separate items based on their size or mass. The most advanced technique is automated machine vision grading, which utilizes high-speed cameras to capture images of the produce from multiple angles. Specialized software then analyzes these images to calculate precise dimensions and evaluate the shape against an ideal template.

Ensuring uniform size and shape is vital because it simplifies the packing and shipping process, maximizes the use of carton space, minimizes damage during transit, and crucially, helps establish consistent packing and pricing options that meet specific customer and market expectations.

Defects

In fresh produce quality control, a defect is any physical characteristic or condition that causes a fruit or vegetable specimen to fall below the minimum specified quality standard for its intended grade or market. These issues can be caused by various factors, including growth problems (e.g., scarring, sunburn), post-harvest damage (e.g., bruising, cuts, stem punctures), or the presence of disease or decay, all of which negatively impact the product's appearance, edibility, or shelf life.

Often resources for scouting and spotting defects are made for specific commodities by governmental agencies and univeristy extension programs. QC staff are trained on the most common defects to look for based on the crop and the growing location and then must assess if the defect damage is at an acceptable level for a specific grade. Fresh produce defects can generally be grouped into the following categories:

Growing defects

Growing defects occur as a result of environmental factors that affect the shape, size, appearance, or texture of the fruit. Some of the most common growth defects are:

- Sunburn or sun damage is especially common in fruit that are suddenly exposed due to defoliation. Sun damage may cause visible discoloration and texture damage. Affected areas are more susceptible to rot or fungal growth.

- Over or underwatering may affect the shape and uniformity of fruit, or cause damage like splitting or scarring.

- Scarring damage may occur during the growth period due to changes in temperature, humidity, moisture, or growing position.

- Limb rub is a common deficiency in apples that occurs when a growing fruit is pressed too closely to a twig or branch, causing a distinctive scar.

- Zippering in tomatoes refers to the appearance of thin zipperlike scars that may extend all the way from the stem to the bottom of the tomato. Zippering is a common defect that occurs due to high humidity during the pollination process.

- Pest or disease damage defects occur during growing when pest pressure rises during the season and is not eliminated before fruit is damaged or when the tree health is compromised by an infection.

Picking defects

Picking defects occur during harvest and are typically caused by rough handling. While many harvest defects may appear small or innocuous, any wound or damage to fruit may leave it open to a secondary infection or infestation.

- Stem punctures are one of the most common picking defects found in apples. Stem punctures are wounds received from the fruit’s stem, or from the stem of another fruit it is harvested or stored with.

- Clipper damage wounds occur during harvest and pruning when a worker may puncture or scratch fruit if they are not handled carefully.

- Bruising is probably the most common type of damage as it occurs from rough handling, bin transportation, bumps and pressure from other fruit, and can occur at any step along the supply chain. Bruising on fruit may be visible immediately or take as long as a full day to appear. The more times a bin of fruit is moved, even the number of times a piece of fruit is touched by hand, the more likely bruising can occur and contribute to loss of otherwise viable fruit.

Storage defects

Even after the harvest, transportation and sorting are done, stored fruit and vegetables aren’t immune to damage. Climate-controlled storage presents its own set of issues and risks. Storage disorders affect produce in long term storage and may produce undesirable flavors, affect texture, or even cause visible damage. These disorders include various kinds of storage rot and fungal development, as well as other physiological disorders.

- Gray Mold, also known as Botrytis Blight, is one of the most common types of mold affecting fruit and vegetables. Botrytis is a fungal disease that spread grey fungal spores over the surface of affected produce.

- Bitter pit is an apple and pear disorder characterized by browning and spot development from calcium deficiency (a growing defect) but is often not detectable until the fruit has been in storage. Honeycrisp apples are extremely susceptible to bitter pit.

- Chilling injuries occur, as you might have guessed, when fruit or vegetables are stored at low temperatures. While we are all familiar with the concept of freezer-burned frozen berries, chilling injuries can occur well above freezing temperatures. Symptoms of chilling injuries vary depending on the product, but typically start with discoloration and texture issues due to tissue damage.

- Carbon dioxide burns affect fruit in controlled atmosphere storage, where the oxygen is pumped out of the storage unit to increase the shelf life.

What is grading?

Produce grading is the systematic process of sorting fresh fruits and vegetables into distinct classes based on measurable quality parameters, which include appearance, precise dimensions (size and shape), characteristic pigmentation (color), texture (firmness), and, critically, the absence of defects or flaws. Grading involves categorizing the produce—often into designations like U.S. No. 1 or Extra Class—to ensure consistency and meet specific market expectations. These quality control measures strictly adhere to detailed standards set by regulatory bodies (like the USDA or EU), industry associations, or individual market requirements.

Examples in Practice

- Apples: For high-grade fresh-market apples, the standard is extremely demanding. A U.S. Extra Fancy apple must have excellent color coverage, be virtually free of defects, and possess a "well-formed" shape characteristic of the variety. A minor defect, such as a small surface bruise or a slight hail mark, might cause the apple to be downgraded to a U.S. No. 1 grade. Apples with more significant damage, misshapen forms, or excessive scarring are often relegated to a lower grade, suitable only for processing (e.g., juice or sauce).

- Tomatoes: In the grading of processing tomatoes, the criteria focus heavily on firmness and the level of ripeness/color, as these attributes dictate efficiency in the canning or pasteurization process. Conversely, fresh-market tomatoes must also meet strict size and shape standards for packing, but firmness is paramount to withstand shipping. A tomato that is too soft or has cracks/puffs (internal defects) will be rejected from the premium grade because it would spoil quickly and damage neighboring produce in the carton, thus failing the quality control standards.

These standards define the acceptable range of variation for various produce types and are essential for facilitating international trade, establishing price points, and ultimately, ensuring consumer satisfaction and trust.

Sensory evaluation

A quick note about the simplest and perhaps most common starting place when it comes to fresh produce quality control: taste testing! These quality checks rely on the senses of sight, smell, touch, and sometimes taste to evaluate the quality and freshness of produce. Sensory evaluation can provide valuable information about the qualitative characteristics of fruits and vegetables, helping to determine their ripeness, texture, and overall desireability for sale. During sensory evaluation, quality control inspectors examine the produce visually, looking for any external defects such as discoloration, bruises, cuts, or blemishes. They assess the overall appearance, including color, size, shape, and uniformity, as these attributes are often associated with quality and consumer preference.

While sensory evaluation is a valuable tool, it's important to acknowledge that it has inherent subjectivity. The perception of sensory attributes can vary among individuals, and personal preferences may influence evaluations. To mitigate this subjectivity, sensory panelists undergo training to develop a common vocabulary and understanding of quality attributes. Standardized evaluation protocols and reference samples are often employed to minimize variability.

Key storage and environmental Quality Control metrics

Post harvest, after fresh produce products has been inspected for core quality metrics, a large part of continued quality control is about monitoring the environment the fruit is stored in. Optimal storage conditions will of course vary depending on the fruit or vegetable largely depending on how the fruit ages. Before we dive into the metrics to monitor, we have defined some key terms in fresh produce maturity and storage manegement.

Fresh produce maturity and storage terms defined

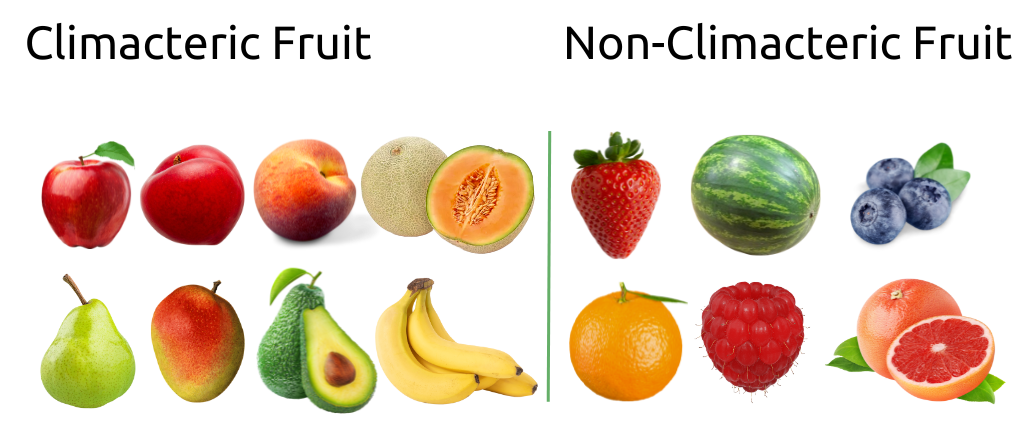

Climeractic vs. Non-climeractic

Put simply, Climacteric fruit like apples continue to ripen after they are picked. These fruits will continue to ripen in storage or during transportation after harvest. Climacteric fruit produce more ethylene than non-climacteric fruit like strawberries, which won't become fully ripe after separation from the plant.

Climeractic fruit can be harvested immature (but not fully unripe) and then ripened on demand during storage or transit. Storage management focuses on reducing ethylene levels (using scrubbers or controlled atmosphere) and lowering temperature to delay this climacteric surge and extend storage life.

Non-climeractic fruit must be harvested when they are fully ripe because they will not significantly improve in quality after picking. Storage management focuses on minimizing water loss and decay, as ethylene exposure will simply accelerate senescence without improving ripeness.

Senescence

Senescence is the final, irreversible stage of aging in fresh produce, following maturation and ripening, characterized by a breakdown of the fruit cell components and loss of quality. Visually, it manifests as yellowing, softening, loss of crispness, and increased susceptibility to decay. All post-harvest quality control techniques, such as cooling, humidity control, and controlled atmosphere storage, are ultimately designed to delay the onset of senescence for as long as possible.

Respiration

Respiration is the metabolic process in which stored organic materials (like sugars and starches) within the plant cells are broken down using oxygen (O2) to release energy, carbon dioxide (CO2), and heat. It is essentially the produce "breathing." The respiration rate is inversely related to shelf life. Produce with a high respiration rate, like broccoli, asparagus and sweet corn, means the produce is consuming its stored food reserves, generating a lot of heat of respiration that must be continuously removed by cooling. These products deteriorate quickly, resulting in rapid loss of sugar, firmness, and nutritional value, demanding immediate and rigorous cold chain management to slow this rate. Low respiration rate crops, like apples, potatoes and citrus, have a slower metabolism, allowing for much longer storage periods when maintained under optimal conditions. Storage and Quality Control management seek to keep the respiration rate as low as possible for longer storage life.

Cold storage

Cold storage is the storage method for the preservation of most fresh produce products. It relies primarily on maintaining a low, consistent temperature (just above the freezing point of the produce) and often high relative humidity. Lowering the temperature drastically slows down the respiration rate and metabolic processes of the fresh produce, delaying ripening and the onset of senescence. The low temperature also inhibits the growth of spoilage microorganisms.

Controlled Atmosphere (CA) storage

Controlled Atmosphere (CA) storage is a more advanced technique that uses cold storage as its foundation, but supplements it with rigorous gas management within a sealed, airtight room. In CA rooms, temperature, humidity, Oxygen (O2), Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and often Ethylene (C2H4) are closely monitored and controlled.

CA storage creates a state of controlled dormancy for the fruit inside by actively reducing the oxygen level (typically from 21% down to 1% - 5%) and sometimes slightly increasing the carbon dioxide level. This manipulation of gas composition slows the respiration rate beyond what temperature alone can achieve. The removal of ethylene, the ripening hormone, further inhibits maturation.

This process is used mainly for long-term storage of climacteric fruits like apples and pears, allowing them to be harvested in the fall and marketed year-round while retaining their firmness and quality for 2 to 4 times longer than in standard cold storage. CA requires sophisticated equipment like nitrogen generators and CO2 scrubbers for continuous monitoring and adjustment.

Environmental montoring metrics and methods

Temperature monitoring

Monitoring storage temperatures is vital to ensure a slowed respiration rate and to inhibit the growth of bacteria and mold. Maintaining the optimal low temperature is the single most effective way to delay senescence and preserve firmness.

Continuous temperature monitoring uses thermocouples or digital sensors placed within the produce bins, in transport containers, and on the walls of the storage facility. Effective Quality Control processes will ensure the temperature stays within the narrow, ideal range for the specific commodity, avoiding both freezing and chilling injury thresholds. Some monitoring systems will integrate automatic temperture data logging systems so this record does not have to be a manual process and can be monitored remotely.

Humidity monitoring

Humidity monitoring during storage is primarilty to prevent water loss (dessication), which will lead to wilting, shriveling and shrinkage, and a loss in quality and marketability ultimately.

Humidity monitors (like hygrometers) will return a Relative Humidity (RH) score. In many fresh produce storage environments, the goal is to maintain high humidity (90-98%), usually this is acheived with humidifier systems or some old fashioned floor wetting.

Gas monitoring

These three gases are primarily monitored in Controlled Atmosphere (CA) storage to induce a state of dormancy beyond what cold temperatures alone can achieve.

- Oxygen (O2)

- Lowering O2 levels in storage to between 1% - 5% will dramatically surpress a fruit or vegetable’s respiration rate. Levels are monitored using electrochemical sensors or paramagnetic oxygen analyzers. The levels must be precisely controlled; levels that are too high negate the benefit, while levels that are too low can cause anaerobic respiration, leading to off-flavors (fermentation) and internal damage.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

- Adding CO2 to a storage environment inhibits fruit respiration and sometimes surpresses the effects of ethylene. CO2 levels are usually kept between 1%-5% and are monitored using Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR) sensors. If CO2 levels are too high, it will cause fruit injury, like internal browning in apples.

- Ethylene (C2H4)

- Ethylene (C2H4) is a naturally occurring plant hormone, often called the fruit-ripening hormone. To test ethylene gas concentration on the fruit itself, fruit are sealed in an airtight container, allowing the ethylene to build up. After some time has passed, the gas inside the container is extracted and measured with a gas chromatograph. Gas chromatography is used in analytical chemistry to separate and analyze gas compounds. In apples, a gas sample can be taken by inserting a needle directly into the core of the apple.

- When monitoring C2H4 in the storage environment atmosphere, integrated gas chromatography systems or photoionization detectors (PIDs) maintain consistent monitoring over time. In CA storage, C2H4 levels are levels are often actively kept near zero using catalytic converters or scrubbers (like potassium permanganate) to ensure the longest possible storage window.

Advanced & non-destructive Quality Control testing

Many of the core Quality Control metrics defined above rely on manual tools and methods and are often time consuming, destructive and error prone. But as automation and AI technology is applied to QC processes, some new, less subjective and less destructive tools have become more popular.

Near-Infrared (NIR) spectrocopy and DA meters

Near-Infrared (NIR) testing and the specialized DA meter are newer technology in fresh produce quality control. They use non-destructive quality control methods, making them an attractive option for in field and higher speed testing. NIR spectroscopy quantifies multiple internal properties simultaneously, such as Brix (soluble sugars), dry matter, and organic acids, by analyzing how the produce absorbs specific wavelengths of light.

The DA meter is a specific NIR tool that measures chlorophyll content using the Index of Absorbance Difference (IAD) to objectively monitor fruit ripeness and maturity. Both offer fast, objective results about fruit maturity and quality that reduce waste, enabling efficient sampling and ensuring consistency across the supply chain.

Portable computer vision defect detection and grading tools

Portable AI-driven Quality Control (QC) tools are becoming more popular as the technolgy driving them becomes more accurate. These solutions leverage computer vision and machine learning (AI) on handheld devices (like smartphones or tablets) to provide instant, objective, and consistent analysis of produce quality, often working directly in the field, packhouse, or receiving dock without requiring constant internet connectivity. The core process involves an inspector taking a photo of a sample (e.g., a bin of apples or a box of tomatoes); the device's AI model then instantly analyzes external attributes like size and color distribution.

The shift to these digital, portable tools delivers several key benefits for quality control and the overall supply chain. First, they dramatically standardize grading, removing the inherent bias and inconsistency that comes with human fatigue or varied training across inspectors and global sites.

Second, they provide real-time, actionable data on product quality and quantity, which helps decision-makers make crucial, timely choices, such as prioritizing which bins to ship first, optimizing storage locations, or setting appropriate prices. Verified, timestamped digital documentation of the produce's condition at the source helps to minimize costly disputes and rejection rates between exporters and importers, turning quality control from a reactive process into a proactive, transparent system that ultimately reduces food waste and maximizes profitability.